REFERENCE BASELINE VALUES FOR CALCANEAL QUANTITATIVE ULTRASOUND PARAMETERS IN NIGERIAN CHILDREN: RELATIONSHIP WITH BODY MASS INDEX AND SERUM CALCIUM

Main Article Content

Abstract

Objective: This study aimed to establish reference baseline values for calcaneal Quantitative Ultrasound Index (QUI) and Estimated Bone Mineral Density (eBMD) in healthy Nigerian children. It also investigated the relationship between BMI, serum calcium levels, and bone density.

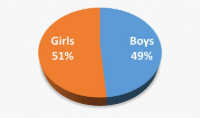

Methods: The Sahara bone sonometer was used to measure the QUS parameters of 494 boys and 522 girls in this cross-sectional study. The participants' BMI and serum calcium levels were also measured. Pearson correlation coefficients and a multiple regression model were employed for the test of association and relationship.

Results: Baseline measurements of QUI and eBMD were available in boys with a mean (SD) age of 11.38 (2.32) years, and girls, with a mean (SD) age of 11.47 (2.92) years. The participants' mean QUI and eBMD (SD) were 94.91 (13.37) and 0.52 (0.08) g/cm², respectively, for boys and 92.46 (13.47) and 0.51 (0.09) g/cm² for girls. In both genders, age was a predictor of both QUI and eBMD (p < 0.05) while BMI was a predictor of both QUI and eBMD in only the girls (p < 0.05). Serum calcium had no relationship with the two QUS parameters (p > 0.05).

Conclusion: The study is the first to fill a critical gap in pediatric bone health data by establishing baseline QUI and eBMD values in Nigerian children.

Downloads

Article Details

Section

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

All articles in JRRS are published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0). This permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

How to Cite

References

1. Madimenos FC, Snodgrass JJ, Blackwell AD, Liebert MA, Cepon TJ, Sugiyama LS. Normative calcaneal quantitative ultrasound data for the indigenous Shuar and non-Shuar Colonos of the Ecuadorian Amazon. Arch Osteoporos. 2011;6(1-2):39-49.

2. Alonge TO, Adebusoye LA, Ogunbode AM, Olowookere OO, Ladipo MA, Balogun WO, OkojeAdesomoju V. Factors associated with osteoporosis among older patients at the Geriatric Centre in Nigeria: a cross-sectional study. S Afr Fam Pract. 2017;59(3):87-93.

3. Atiase Y, Quarde A. A call to action for osteoporosis research in sub-Saharan Africa. Ghana Med J. 2020;54(1):58-67.

4. Njeze NR, Ikechukwu O, Miriam A, Olanike AU, Akpagbula UD, Njeze NC. Awareness of osteoporosis in a polytechnic in Enugu, South East Nigeria. Arch Osteoporos. 2017 Dec;12(1):51. doi: 10.1007/s11657-017-0342-

3. Epub 2017 May 24. PMID: 28540650.5. Baroncelli GI. Quantitative ultrasound methods to assess bone mineral status in children: technical characteristics, performance, and clinical application. Pediatr Res. 2008;63:220-28.

6. Fielding KT, Nix DA, Bachrach LK. Comparison of calcaneus ultrasound and dual X-ray absorptiometry in children at risk of osteopenia. J Clin Densitom. 2003;6:7-15.

7. Sioen I, Mouratidou T, Herrmann D, De Henauw S, Kaufman JM, Molnár D, et al. Relationship between markers of body fat and calcaneal bone stiffness differs between preschool and primary school children: results from the IDEFICS baseline survey. Calcif Tissue Int. 2012;91(4):276-85.

8. Specker BL, Schoenau E. Quantitative bone analysis in children: current methods and recommendations. J Pediatr. 2005;146(6):726-31.

9. Zemel BS, Leonard MB, Kelly A, Lappe JM, Gilsanz V, Oberfield S, et al. Height adjustment in assessing dual energy x-ray absorptiometry measurements of bone mass and density in children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(1):82-90.

10. Bachrach LK. Acquisition of optimal bone mass in childhood and adolescence. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2001;12:22-8.

11. Berger C, Goltzman D, Langsetmo L, Joseph L, Jackson S, Kreiger N, et al. J Bone Miner Res. 2010 Sep;25(9):1948-57.

12. Gordon CM, Zemel BS, Wren TA, Leonard MB, Bachrach LK, Rauch F, et al. The determinants of peak bone mass. J Pediatr. 2017;180:261-69.

13. Carey DE, Golden NH. Bone health in adolescence. Adolesc Med State Art Rev. 2015;26(2):291-325.

14. Rizzoli R, Bianchi ML, Garabedian M, et al. Maximizing bone mineral mass gain during growth for the prevention of fractures in adolescents and the elderly. Bone. 2010;46(2):294-305.

15. Baxter-Jones AD, Faulkner RA, Forwood MR, Mirwald RL, Bailey DA. Bone mineral accrual from 8 to 30 years of age: an estimation of peak bone mass. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(8):1729-39.

16. Nwogu UB, Agwu KK, Anakwue AMC, Okeji MC, Idigo FU, Ogbu SOI. Calcaneal broadband ultrasound attenuation and speed of sound measurements in a population of Nigerian children: reference data and the influence of sociodemographic variables. J Ultrasound Med. 2019;38(5):1349-60.

17. Guglielmi G, de Terlizzi F. Quantitative ultrasound in the assessment of osteoporosis. Eur J Radiol. 2009;71(3):425-31.

18. Barkmann R, Laugier P, Moser U, Dencks S, Padilla F, Haiat G, et al. A method for the estimation of femoral bone mineral density from variables of ultrasound transmission through the human femur. Bone. 2007;40:37-44.

19. Gerdhem P, Dencker M, Ringsberg K, Akesson K. Accelerometer-measured daily physical activity among octogenarians: results and associations to other indices of physical performance and bone density. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2008;102:173-80.

20. Nayak S, Olkin I, Liu H, Grabe M, Gould MK, Allen IE, et al. Meta-analysis: accuracy of quantitative ultrasound for identifying patients with osteoporosis. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:832-41.

21. Zhu ZQ, Liu W, Xu CL, Han SM, Zu SY, Zhu GJ. Ultrasound bone densitometry of the calcaneus in healthy Chinese children and adolescents. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:533–41.

22. Maggio AB, Belli DC, Puigdefabregas JW, et al. High bone density in adolescents with obesity is related to fat mass and serum leptin concentrations. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;58:723–8.

23. Laabes EP, VanderJagt DJ, Obadofin MO, Sendeht AJ, Glew RH. Assessment of the bone quality of black male athletes using calcaneal ultrasound: a cross-sectional study. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2008;5(1):1–8.

24. Lin JD, Chen JF, Chang HY, Ho C. Evaluation of bone mineral density by quantitative ultrasound of bone in 16,862 subjects during routine health examination. Br J Radiol. 2001;74:602–6.

25. Alghadir AH, Gabr SA, Al-Eisa E. Physical activity and lifestyle effects on bone mineral density among young adults: sociodemographic and biochemical analysis. J Phys Ther Sci. 2015;27(7):2261–70.

26. Omar A, Turan S, Bereket A. Reference data for bone speed of sound measurement by quantitative ultrasound in healthy children. Arch Osteoporos. 2006;1:37–41.

27. Yesil P, Durmaz B, Atamaz FC. Normative data for quantitative calcaneal ultrasonometry in Turkish children aged 6 to 14 years: relationship of the stiffness index with age, pubertal stage, physical

characteristics, and lifestyle. J Ultrasound Med. 2013;32(7):1191–7.

28. Cole ZA, Dennison EM, Cooper C. Osteoporosis epidemiology update. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2005;31(4):681–703.

29. Zaini WM, Ariff M. Bone mineral density assessment in pre- and postmenopausal women: comparison between T scores by heel QUS and DXA in HRPZII. Med J Malaysia. 2012;67:487–90.

30. Nwogu UB, Agwu KK, Anakwue AMC, Idigo FU, Okeji MC, Abonyi EO, et al. Bone mineral density in an urban and a rural children population—A comparative, population-based study in Enugu State, Nigeria. Bone. 2019;127:44–8.

31. Chin KY, Ima-Nirwana S. Calcaneal quantitative ultrasound as a determinant of bone health status: what properties of bone does it reflect? Int J Med Sci. 2013;10(12):1778–83. doi:10.7150/ijms.6765.

32. Fitzgerald GE, Anachebe T, McCarroll KG, et al. Calcaneal quantitative ultrasound has a role in out ruling low bone mineral density in axial spondyloarthropathy. Clin Rheumatol. 2020;39:1971–9. doi:10.1007/s10067-019-04876-9.

33. Han CS, Kim HK, Kim S. Effects of adolescents’ lifestyle habits and body composition on bone mineral density. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(11):6170.

34. McVey MK, Geraghty AA, O’Brien EC, et al. The impact of diet, body composition, and physical activity on child bone mineral density at five years of age—findings from the ROLO Kids Study. Eur J Pediatr. 2020;179:121–31. doi:10.1007/s00431-019-03465-x.

35. Xiao P, Cheng H, Wang L, Hou D, Li H, Zhao X, et al. Relationships for vitamin D with childhood

height growth velocity and low bone mineral density risk. Front Nutr. 2023;10:1081896.

36. Ellis KJ, Shypailo RJ, Wong WW, Abrams SA. Bone mineral mass in overweight and obese children: diminished or enhanced? Acta Diabetol. 2003;40:274–7.

37. Leonard MB, Shults J, Wilson BA, Tershakovec AM, Zemel BS. Obesity during childhood and adolescence augments bone mass and bone dimensions. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:514–23.

38. Nagasaki K, Kikuchi T, Hiura M, Uchiyama M. Obese Japanese children have low bone mineral density after puberty. J Bone Miner Metab. 2004;22:376–81.

39. Cormack SE, Cousminer DL, Chesi A, et al. Association between linear growth and bone accrual in a diverse cohort of children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(9) doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.1769.

40. Bonjour JP, Gueguen L, Palacios C, Shearer MJ, Weaver CM. Minerals and vitamins in bone health: the potential value of dietary enhancement of bone health and targeting preventive measures in adolescents. J Nutr. 2009;139(9):1916S–20S.

41. Vanderschueren D, Laurent MR, Claessens F, et al. Sex steroid actions in male bone. Endocr Rev. 2014;35(6):906–60.

42. Elgán C, Fridlund B. Bone mineral density in relation to body mass index among young women: a prospective cohort study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2006;43:663–72.

43. Felsenfeld AJ, Levine BS. Calcitonin, the forgotten hormone: does it deserve to be forgotten? Clin Kidney J. 2015;8(2):180–7.

44. Misra M, Katzman DK, Clarke D. Calcium and bone metabolism in children and adolescents with eating disorders. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2008;6(1):42–8.

45. Braillon PM, Bouzitou A, Cortet B, Royer M, Slosman DO. Serum calcium, phosphate, parathyroid hormone, and vitamin D determinants of bone mineral density in children. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16(2):313–7.

46. Pan K, Tu R, Yao X, et al. Associations between serum calcium, 25(OH)D level and bone mineral density in adolescents. Adv Rheumatol. 2021;61:16. doi:10.1186/s42358-021-00174-8.

47. Alghadir AH, Gabr SA, Al-Eisa E. Physical activity and lifestyle effects on bone mineral density among young adults: sociodemographic and biochemical analysis. J Phys Ther Sci. 2015;27(7):2261–70.

48. Qu Z, Yang F, Yan Y, Hong J, Wang W, Li S, et al. Relationship between serum nutritional factors and bone mineral density: a Mendelian randomization study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(6) –43. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgab085.

49. Sit D, Kadiroglu AK, Kayabasi HE, et al. Relationship between bone mineral density and biochemical markers of bone turnover in hemodialysis patients. Adv Ther. 2007;24:987–95.

50. Cerani A, Zhou S, Forgetta V, et al. Genetic predisposition to increased serum calcium, bone mineral density, and fracture risk in individuals with normal calcium levels: a Mendelian randomisation study. BMJ. 2019;366: l4414.